Who are you writing for? Know your children's fiction audience

- Becky Grace

- Oct 12, 2022

- 7 min read

Here we explore the importance of knowing who you're writing for and how understanding your audience will influence your story.

Writers of children's fiction certainly have a unique challenge. Not only do we have to know our picture books from our young adult books, but we also need to understand children today. It's not enough to say 'we were kids once'; children and childhood are very different now compared to our own childhood.

Books today need to compete with screens, devices, dozens of internet and TV channels. Books need to be engaging and entertaining to a whole new level! If you can't hold a child's interest, they will put the book down and turn to a screen.

So how do we hold their attention? We need to know them. What do they want from great children's fiction? What issues and interests speak to children today? What are the genres that most excite our young people? Which contemporary writers are the readers' favourites?

Knowing who our audience is and what it is they want from a good book will help us understand how to craft thrilling children's stories.

The Age of Your Audience

Children's fiction covers a wide range of ages. Not as broad a range as adult fiction, true, but children's fiction is special in that each stage requires a different approach. From storylines and themes, to language choice and word count, readers of children's fiction need and want very different things depending on their age and stage in their reading journey.

Consider your own work. Are you writing a rhyming picture book for parents to read to small children with themes around family, fantasy and early learning?

Or are you keen to write a book for children at the beginning of their independent reading journey, perhaps an 'early reader' book or first chapter book with simple themes and an uncomplicated storyline?

Is your story more suited to middle grade readers where the protagonist faces upsets, challenges and a real antagonist through more complex storylines?

Or are you writing for older children – whether teen or YA – where themes really start to develop, characters have more gritty experiences, and romance, mental health and death are explored in a more visceral way?

Knowing the intended age range of your audience is vital to ensuring your story is pitched at the right level, both in terms of interest and reading ability, as well as appropriateness of themes. For more guidance on the difference between the age ranges for children's fiction, read our blog post on Middle Grade vs. YA.

Sometimes it isn't enough to simply identify your story as Middle Grade or YA. Just think about the age ranges within those categories. The ages of YA readers, for instance, can range from twelve to eighteen, and what is appealing to and suitable for an eighteen-year-old will probably not be appealing to and suitable for a twelve-year-old.

The same is true for middle grade readers, who can range in age from seven or eight to twelve.

When you say 'I'm a children's writer' people often assume that you write for tiny tots, as if children weren't of all ages. They seldom ask, 'What age of children?' – Cathy MacPhail

Take two of my favourite middle grade reads: Libby and the Parisian Puzzle by Jo Clarke, and

The Clockwork Sparrow by Katherine Woodfine.

Both middle grade books, both listed as suitable for ages 9+, but very different in nature. Libby and the Parisian Puzzle weighs in at just under 30,000 words, while The Clockwork Sparrow hits 66,000 words. Libby, Jo Clarke's protagonist, is eleven years old; Sophie, Katherine Woodfine's protagonist, is fourteen. The Parisian Puzzle is set in a school but The Clockwork Sparrow is set in a work environment.

There are differences in the stakes (what's at risk if the protagonist doesn't succeed) and the level of peril the protagonist faces. Both are approached correctly for their particular intended audience.

The same can also be said of the language each author uses. Jo Clarke chooses to employ simpler vocabulary and sentence structure which makes her story wonderfully accessible to early middle grade readers of eight or nine.

Katherine Woodfine has chosen language and syntax that is more complex and challenging, perfect for middle grade readers at the upper end of the age range with greater confidence in reading.

The best advice I could give you here is to read both books! Firstly, read them to enjoy them. Secondly, read them analytically. Look at the differences between them and identify those areas that would make them suitable for readers at different points of the middle grade stage. Consider their use of language, the point of view used, the complexity or simplicity of the storyline. How can these books help you identify your own intended audience?

The Genre of Your Story

What does genre have to do with knowing your audience? Very often, readers have favourite genres. Perhaps a middle grade reader is particularly fond of mysteries and detective stories. Maybe a YA reader has a preference for dystopian fantasy or sci-fi. Understanding genre is about knowing the conventions of that genre.

And by conventions, I don't mean rules. There should be no rules in crafting stories – be original, be unique, push boundaries, bend logic – but conventions are slightly different.

If a fan of mysteries and crime capers picks up a copy of Murder Most Unladylike by Robin Stevens, they will be expecting certain things. A crime (in this case a murder). Some mystery. Suspects. Clues. Detectives. Intrigue, suspense, tension. If these elements are missing from the story the reader will be disappointed.

A reader looking for fantasy and adventure would pick up Tola Okogwu's Onyeka and the Academy of the Sun expecting to see a reluctant hero's quest for power or knowledge, good vs. evil, a protagonist learning to harness new powers, world building, or magic. Not all of these need to be present all of the time, but knowing the conventions of a genre helps you understand what your readers are expecting.

Tola Okogwu's Onyeka is a superb example of following broad conventions but still remaining totally distinctive. Simon and Schuster, the publishers, hailed Onyeka as 'Black Panther meets Percy Jackson' describing it as an 'action-packed and empowering middle-grade superhero series about a British-Nigerian girl who learns that her Afro hair has psychokinetic powers'. Original and unique, but offering readers the classic conventions of a fantasy adventure.

Making it Fun

As a children's writer, perhaps the most important thing to remember about children is that they want fun! Admittedly, 'fun' is quite a subjective word. Does it mean the kind of fun Daisy and Hazel have in Murder Most Unladylike? Sure, they're investigating murder, but they have fun doing it! There's an adventure, there are friends, there's the feeling of getting one over on the grown-ups and solving the crime before they do.

Or does it mean the kind of irreverent fun that children love in The Brilliant World of Tom Gates series by Liz Pichon, the numerous The Treehouse Books by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton, anything ever written by David Walliams, or - from our own childhood - Roald Dahl?

Like his books or loathe them, there's no denying that David Walliams knows how to reach his audience. He just gets them. His books can entice the most reluctant of readers to pick up a hardback and settle down for a guffaw. He entertains them.

A good children's book is accessible and thought-provoking, and sometimes a good children's book is just a lot of fun – Catherine Johnson

There are different ways of approaching fun, and sometimes the themes of a book don't allow for much hilarity. That's fine, don't shoehorn it in where it doesn't belong. But you must at least entertain the reader and capture their imagination. If you don't, they will probably put the book down and reach for Gangsta Granny.

What Sells?

Do you know which books are on the children's bestseller list this week? Do you know which children's book was Christmas #1? Do you know who the highest paid children's author is?

Does it even matter? Should we be concerned about tailoring our story for the children's book market or should we stick with our story exactly as we envision it?

Obviously, you should write the story you want to write, one that you're passionate about and invested in. But if you want to write a book that also has commercial potential, you need to know what's selling well and what children are reading and enjoying.

Make it your business to know what's being published. Pop along every couple of weeks to your local Waterstones or independent bookshop, look at the window displays, ask staff about the new releases. Look online, follow children's publishers on Twitter, read the industry news about children's books and authors.

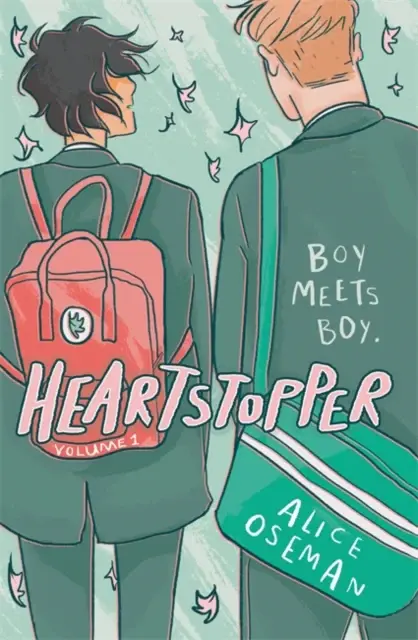

Did you know about the buzz around the commercial potential of Skandar and the Unicorn Thief by A. F. Steadman? Were you aware of the loyal, active and powerful fanbase of Alice Oseman's Heartstopper books? Have you heard about the children's books that have been picked up for TV or film such as Onyeka and Skandar?

A Final Thought...

Always think about your motivation for writing a children's book. Why are we writing? To entertain, to bring joy, to develop minds. For that to happen, we need to hold a child's interest. And for that to happen, we need to know what a young reader today finds interesting. Don't discard the classics and the books from your own childhood; they have value and have earned their place. But don't rely solely on them. To say you know children's literature because you read books as a child isn't enough. Stretch yourself beyond those books and dive right into the treasure trove of children's books written today,

Suggested reading:

Libby and the Parisian Puzzle by Jo Clarke

The Clockwork Sparrow by Katherine Woodfine

Guide to Writing For Children and YA (Writers' and Artists') by Linda Strachan

The Magic Words: Writing Great Books for Children and Young Adults by Cheryl B. Klein

Murder Most Unladylike by Robin Stevens

Onyeka and the Academy of the Sun by Tola Okogwu

The Brilliant World of Tom Gates by Liz Pichon

The Treehouse Books by Andy Griffiths and Terry Denton

Space Boy by David Walliams

Skandar and the Unicorn Thief by A. F. Steadman

Heartstopper by Alice Oseman

Quotes taken from Guide to Writing For Children and YA (Writers' and Artists') by Linda Strachan

Comments